The sun hadn’t set, but shadows couldn’t get much longer. That concerned Mike a little. In sunlight, he could see more than most who were legally blind, and in darkness, bright storefronts and streetlights could guide him, at least keep him on the sidewalk. But this was dusk, when the light was lowest. Sunlight was fading. Streetlights weren’t lit, and beyond the sidewalk, many lights were moving. Those lights were being pushed by a ton of metal, on four wheels or more. Mike kept walking.

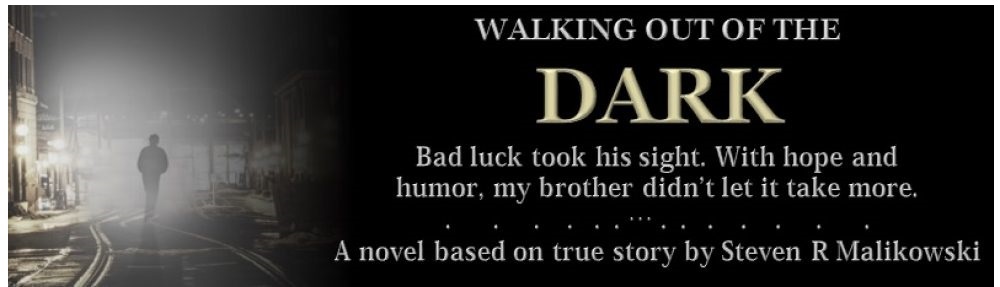

The temperature was going down with the sun, so Mike shoved his hands deeper into his parka. He noticed the blurry image of two blinking neon signs. They reminded him of something his counselor had said last week. “This road connects Bridgman School for the Blind to Mariner’s Motel, which’ll be your home for a while. Mariner’s is two blocks from those two blinking signs. Like I’ve been saying, you need to use your memory for things your eyes used to do, like making sense out of a disorganized world. Fortunately, there’s a lot of room for improvement.”

Mike stopped thinking about his counselor and focused on the two signs. Even though they looked like a blinking haze, Mike could tell that one was orange. He knew this color, especially in neon. It was a familiar sight. After all, he enjoyed going to bars as much as any other guy in his twenties. The color of the other sign was less familiar, less clear. Mike thought it might be blue, maybe purple. He hadn’t seen a blue or purple one before, so he wondered what it looked like. The only way to find out would be to get within a few inches of the sign, stop walking, and move his head around it, to slowly examine the sign. Unfortunately, that would draw more attention to himself than he wanted, especially in this neighborhood. He kept walking.

Still thinking about old orange neon signs and new neon signs, his head snapped toward the street. A horn blared, and a man shouted, “Idiot!” Mike didn’t know what had happened. The horn and shouting had probably come from a careless driver who’d crossed paths with an obnoxious driver.

Of course, he didn’t drive anymore, but Mike had spent almost a decade behind the wheel. It wasn’t long ago that he’d been a teenager laughing with his friends while driving. Sometimes, they would laugh at the friend who was driving when he tried some creative driving stunt. That usually involved speed, weaving, or something else that had seemed funny at the time. At the moment, on this sidewalk, those stunts concerned him. He thought about the drivers passing him right now. Some of them had their own version of creative driving stunts. Many were in a hurry. Some drove too close to the car in front, and some were driving too close to the sidewalk; at least, it felt that way to Mike.

His thoughts shifted to something his dad had said a few years ago: “There are a lot of things you can do in a bad situation; try to choose something that doesn’t make it worse.”

Mike focused on what he could do. He could see a little. He could hear the cars and trucks, smell them in some cases. Mike could also remain calm and focus on what mattered most. Besides, his vision was supposed to fade in the next few months and years. He had to find ways to live with other people’s mobility or restrict his own. He kept walking.

He started feeling a strange satisfaction. Even when his limited sight was at its lowest, he could be in an uncomfortable situation and stay rational. This was a part of blindness he hadn’t expected, an odd opportunity to be a little brave, maybe even proud. Then he felt something else, something falling out of a back pocket from his blue jeans. His folded white cane had started coming out. He thought about unfolding the long, white cane and using it. At the least, it would show others that he was blind. Mike smiled, tucked it back in, and decided that even proud people were entitled to an unwise decision or two. Besides, he was almost home and was still learning how to use the long cane without hitting people.

It was odd to think about this place as home. Until a week ago, home had been a small house in farm country without sidewalks, buildings, or traffic. Now, he lived in the city of Portage Bay. He had always enjoyed cities, but that was for visiting family or sightseeing. Walking next to a busy road every day didn’t provide the same pleasure.

He slowed down because some shadows were collected in front of him. Each had a familiar shape—five or six feet high, about two feet wide, two narrow pillars on the bottom half, one wide pillar on the top half, and a ball on top. Put together, this was the blurry shape of a person, a group of people in this case. Traffic sounds and smells also increased. The new unleaded gas was the worst, smelling like rotten eggs.

The combination of a group of people and increased traffic usually meant a crosswalk. Being with people at a crosswalk comforted Mike. He was still getting used to living with less sight, and crosswalks concerned him, especially at dusk. Crossing alone could put him on the receiving end of a careless driver.

The group started to move, and he moved with it. As he walked down the next block, there were fewer lights and sounds, which was fine since this long day had started to wear him down. The sun had set a bit more. That made it easier to see city lights but harder to stay warm.

He started thinking about his first week in this new city and the first day of school tomorrow, but he chose to save the thoughts for later. He wanted to return to his room at Mariner’s Motel, get off his feet, and watch some TV.

Mike knew he was getting close to Mariner’s when the greyness he’d been seeing started cycling to lighter shades of grey. The light came from the big sign above the motel’s entrance. His parents had commented on it when they’d brought him here. They thought the sign’s flashing lights were too bright and brash. Mike suspected many people felt the same way, including those driving by him now. They had finished regular jobs and were driving to comfortable homes.

People at Mariner’s were different. If they noticed the sign at all, it was at night when the flashing lights looked even brighter. They stayed in the motel because it was cheap, and it allowed them to leave town for a while, if their work or play made that a good idea. Their play usually involved booze or other drugs. For those who did work, it usually involved something after dark.

“Hey, new guy, back again?”

Mike slowed, mostly out of the manners he’d learned growing up in small-town Minnesota. The question came from Ruby. He was still getting used to talking with someone in her line of work, but since they lived in the same building, it felt right to answer her question.

“Yeah, home sweet home,” he replied, noticing Ruby’s shadow come closer.

“Well, we all know this home isn’t that sweet, but I know some ways to warm it up.”

“You want to loan me your long johns?”

“Honey, you tried that joke last night. Come on now, it’s about time you experienced one of the wonders of our fair city.”

The shadow came even closer. Mike could feel its heat by his cheek. He smelled cigarette smoke and heard a whisper.

“And, since we’re neighbors, I’ll give you my Halloween special, what I call my trick and treat.”

Ruby hadn’t tried that before. Mike lifted his eyebrows, cleared his throat, and took a half-step back, partly because she was bigger than he thought.

“Sorry, honey, I didn’t mean to scare you.”

“That’s okay, Ruby, and, ah, thanks. But, I think I’m just going to watch some TV.”

“Watch some TV? I thought you were blind.”

“I can see a little.”

Ruby’s voice changed from seducing streetwalker to curious neighbor.

“I can’t figure out how someone can see only a little TV and still watch it. It drives me crazy when my TV doesn’t come in right.”

He sighed. “It’s like, let me think.” Mike paused and turned his head, toward the street. At first, he thought about Ruby’s question, but his mind wandered to the change in her voice. When she wasn’t trying to sound sexy, she stretched her vowels. He watched a car slowly pull up and stop. The headlights went dark, but the engine kept running.

“It’s kind of like that,” Mike finally answered, still looking at the car.

“It’s like parking a car?”

Now, he really noticed her vowels, especially the two a-r sounds in her question.

“No, it’s like driving a car with the lights off.”

“In the dark?”

“Unfortunately,” Mike said with a tired sigh.

“That sucks.”

“Yeah, it does,” he replied, hoping the conversation would end soon.

Ruby was quiet for a moment, and he saw her shape get lower, as if she was crouching. She stood up again and said, “I just noticed that a friend of mine is in the car we’ve been talking about.” She changed to her business voice. “I gotta go take care of some things, but you stop by again later if you want. I’ll be around.”

He suspected she wouldn’t be around. Ruby wasn’t like the streetwalkers he saw on TV, but she seemed to keep busy. Mike just hoped they would drive away this time. A couple of nights ago, it had sounded like she was doing her work in a car near his room.

“Okay, Ruby, have a good night.”

He entered Mariner’s Motel and heard the TV behind the desk. He walked toward the sound and rotated slightly to the right when the image of the main desk appeared. After a few steps, he could see the dark frame of a doorway. He walked through it and into a hallway.

Hallways at Mariner’s contained only slightly more light than the sidewalk he’d just walked on. He could tell that some of the wallpaper was missing, but other images were less clear, probably some kind of stains or dents. Mike told himself he didn’t need to waste money on a fancy hotel, so this place was fine. Besides, he’d spent enough time in old cabins to feel comfortable nearly anywhere. Still, he avoided pressing his fingers against the wall for guidance.

His room was on the second floor. The stairs were at the end of the hallway, which he knew was close because he’d passed under two lights in the ceiling. One more light to go. When he’d lost his sight, Mike had worried that climbing stairs was going to be one of those daily challenges that would be frustrating to learn again. Going upstairs turned out to be the easy part. Going down was harder. Sometimes, a foot would roll off the edge of a step, and it was still hard to be sure when he was on the bottom step.

After noticing a third light above him, Mike reached for the handrail, hoped it was cleaner than the walls, and placed a hand on it. He carefully raised a foot to the first step and started climbing the ones after it. When the handrail ended, he walked into the hallway of the second floor.

Mike walked under one light, reached in his left pants pocket for a room key, walked under a second light, and let his right index finger glide along the wall, as lightly as possible. Eventually, Mike felt a doorframe and used it to find the doorknob. Since his right hand was on the doorknob, it was easy to slide his fingers down to the keyhole. He unlocked the door with his left hand, turned the knob, and pushed the door open with his right shoulder.

For years, Mike had relaxed his shoulders after closing his door. Since he’d lost his sight, he relaxed them a little more. In his home, the level of light was consistent. There was no risk of someone running a red light and ruining his day. There were no people who were more interested in his blindness than in him. In his home, he was just Mike again.

After flipping on the light switch, he took off his coat and thought about his previous home. He instinctively stepped to his small fridge, opened it, and took out the stuff for some sandwiches. His previous home was a simple house in the farmlands of Central Minnesota, but it was special. After saving for years, he’d bought the land and helped build the house. Mike made two sandwiches, thick with meat and cheese, on top of the fridge. His home before that was his parents’ house, which was also in the country. After opening the fridge, he put the loaf of bread and other sandwich stuff back inside. His parents’ place was simple too, but it was large enough for them, his three sisters, and his brother. It was also built before they moved in. He took out the cardboard carton of milk, shut the fridge, and picked up the sandwiches. His room in his parents’ house used to seem small and old, but it was larger and newer than the room he was in now.

He walked a few steps to the desk, sat down, bit into a sandwich, and unfolded the spout on top of the milk carton. After drinking out of the carton and taking a few more bites, Mike rotated the desk chair and pushed the plastic power button on his TV. While it warmed up, he finished the first sandwich and drank more out of the carton. A strong voice came from the TV. Mike moved his face close to the screen to see the image more clearly.

“According to a new poll, Gerald Ford continues to close on Jimmy Carter in next week’s general election.”

“Jerk better not win,” Mike said to the television. “Ford’s a crook just like Nixon, running the country without being elected. Politics can’t get any worse.” He bit into the second sandwich, turned the channel selector with a clunk, and heard a milder voice.

“So, visit your Sylvania dealer today to see the next generation of color television.”

Mike mumbled at the TV, “The first generation of color TV did wonders to improve the quality of storylines.” He took another bite and turned the channel again, with another clunk.

“Repeating our top story, a truck driver was killed yesterday while delivering a load of timber in Portage Bay. According to eyewitness reports, the driver honked repeatedly and yelled ‘bad brakes’ out his window. Witnesses also reported that he tried to slow his semi by shifting down. Sadly, the truck broke through the barriers to the lake, and the driver drowned. No other injuries were reported.”

Mike pushed the TV’s power button again to switch the power off. “Tough way to go, bet that water was cold.” After thinking about the driver, his appetite faded, and his glance wandered. First, it went toward the window next to his desk, which had a view of an ally. Next, his glance wandered toward a textbook on his desk, which he wanted to read tonight. After finishing the last sandwich, he brushed some crumbs off the desk, turned on a lamp, and placed the textbook where his sandwiches had been a moment ago.

The book came from his counselor, who’d said it would get him off to a good start. Before coming here, he’d finished a few chapters and became accustomed to reading large print. That used to be only for old people. This textbook was about mobility, learning how to get around a city or building with less sight. He opened the book, reached for a magnifying glass, and read. The heading showed that he was in Chapter 5. He thumbed some pages forward and saw Chapter 7. The pages brushed against his face. He turned some pages back to get to the start of Chapter 6, looked through the glass, and continued reading.

He read a few pages nonstop, but eventually, Mike had to reread some paragraphs. A while later, he read sentences aloud to stay focused. He started to feel warm. The heat in his room was usually too high, and he hadn’t found a way to lower it. He’d asked the people at the front desk to lower the heat a few times. They said they would take care of it “right away.” Mike realized that when Mariner’s staff said “right away,” it meant, “Stop asking for stuff, right away. If you want service, you can go to a more expensive hotel, right away. So, you should let me watch my TV, right away.”

Mike stood up and opened the window. He felt awkward about letting cold air into a heated room, but it was the best option he had. He sat down again and tried finishing Chapter 6, but his mind began to wander. Tomorrow was his first real day at Bridgman School for the Blind. He’d spent some time there during the last few days—getting to know the walking route to the school, finding his classrooms, and filling out forms. He met some people as well. The receptionist introduced him to a guy named Donald, who ran the place. Donald then introduced him to more people, mostly teachers. They seemed nice enough, but something still felt strange about going to your first day of school.

He thought the days of starting school were long over, especially since life had become a familiar routine of work and house projects. A few years ago, he’d taken some classes at a vocational-technical college, but that had been about advancing his skills. This was more like going back to the basics. He started thinking about what would come next, when he was finished with this review of basic skills.

He wanted to return home and pick up with the life he enjoyed in the country, but that was unlikely. Losing his sight meant he couldn’t drive, and living in the country meant driving—to work, to get groceries, and to see friends. He’d worked so hard on building that house. Now, it would have to go. He wondered what else would go and what other new problems would come.

Mike sighed and decided that was enough anxiety for one night; funny how worry usually set in around this time. He closed his book and got ready for bed. Tomorrow and the first day of school would come regardless of how much he worried. Better to face them with a good night of sleep.

. . . . . … . . . . .

Mike paused when he could see the entrance to Bridgman School for the Blind. About a week ago, his counselor had given him a tour of the school and introduced him to some staff, but now, it was real. He checked again that he had his cane, a notebook, and a marker to write with. After thinking about going back to the basics, he shook his head and walked toward the entrance. A comforting thought came to mind: the sooner I start, the sooner I’ll finish.

The receptionist asked a simple yet already familiar question as he entered the school. “Can I help you?”

Mike thought about her level of sight. She always noticed him quickly and seemed aware of subtle movements. He introduced himself, reminded her they might have already met, and said it was his first day.

“Welcome back. Your classes will start in Room 5. Would you like someone to guide you, or would you like directions?”

Mike was feeling independent, so he responded, “I’ll take directions.”

“Continue walking down this hallway until you arrive at a dayroom, which has a TV, a few couches, and a skylight. Walk diagonally through the dayroom, forward and to your left, to another hallway. Room 5 is the second door on the left.”

Mike thanked her and walked down the hallway. Several people were walking or standing, so he tried to look confident, while wondering if he should have asked for a guide. He hoped the dayroom would become obvious. A sound emerged that he couldn’t place. It made him feel concerned, but he still didn’t know what it was. The sound faded, and he looked for the dayroom again, trying to recall the exact words the receptionist had given him.

A loud cry suddenly filled the hallway. Wanting to help, he stopped walking, looked around, and tried finding the source of the sound. He waited and expected someone to rush by or call out instructions. Nothing happened. Other people paused and continued what they were doing, so Mike kept walking. The crying also continued, in waves. It became louder and clearer when he saw sunlight coming from the ceiling. Mike vaguely remembered the receptionist mentioning a skylight. The hallway opened up to a room with couches, decorations on the walls, and a TV. He could see a man crying and others offering comfort. Mike tried to politely ignore the man and walked across the dayroom, toward Room 5.

He found the room easily enough, since a big 5 with an arrow was painted on the wall, pointing to the door. He was still thinking about the crying when a woman asked, “Are you here for the start of classes?”

Mike replied that he was and tried focusing on navigating this room, on starting the first class in his first day at school. But he couldn’t help asking, “Did you hear that?”

“Yes, I heard,” the woman said. She walked into the room with him and added, “That’s one of the things we’re going to talk about. For now, we need to get ready for class. Are you Mike?” He nodded, and she continued. “We have small classes at Bridgman’s, and the other students are already here, at least all the new ones.”

Mike looked at the woman for a moment. She was about ten years older than him and wore a simple dress, which was more formal than other teachers. She was also at least a foot shorter than him, but her disposition wasn’t small. She stood straight and sounded confident.

The two stopped at a round table, where three other students were sitting. Mike said “Hello” to the student on his right and “Good morning” to some students on the other side. He heard responses back but focused on getting seated. He put his notepad on the table and sat down, realizing that his cane was in his back pocket. He leaned to one side, took the cane out, and set it next to his notepad.

The woman who’d greeted Mike at the door made an announcement from behind him. “Normally, we don’t serve coffee in our classes, but we make an exception for these orientation sessions. In a few minutes, we should have some treats from our cooking class. Let me know if you want cream or sugar in your coffee.”

She placed a tray on the table and poured coffee for everyone. He guessed she was a teacher. Mike could see and hear students sip their coffee. He didn’t like coffee but also didn’t want to refuse it and draw attention to himself. He took a small sip and did his best not to cringe at the potent flavor. At least pretending to drink coffee meant that he didn’t have to try and make conversation.

The teacher sat down at the round table and spoke to everyone. “Once again, I want to welcome all of you to Bridgman School for the Blind.” She took a sip from her coffee, and Mike thought she sounded more like a 1950s’ grammar teacher than some of the modern teachers he’d met.

She continued speaking. “We are expecting one more student to arrive, but we’re already running a bit late. My name is Margaret Roberts. I teach the course called Independent Living. Normally, our communication instructor leads this orientation session, but he’s at a conference. I’ll give you an overview of what we’re going to do today, but first, I would like each of you to introduce yourself. I’m not an expert on communication issues for people who have recently lost their sight, but I do know that meeting new people can be challenging. Would anyone like to start?”

Nobody replied.

“In that case, I’ll ask one of you to begin. Norman, would you mind starting?”

“Yeah, why not. I’m Norman Grant. I used to coach high school football in Duluth before the problem with my eyes got worse.”

The words resonated inside a large, fit body. Mike felt them as much as he heard them, since Norman was the student sitting on his right. That voice could easily carry across a football field and instantly correct a wayward player. Apparently, the voice had been used for that purpose for a few years, since it had gravelly tones.

“My blind coach said I should check this place out,” Norman added.

“Your blind coach?” Margaret asked.

“Yeah, sorry, that’s what I call the counselor that State Services gave me. I don’t care for the whole counselor thing, so I call him my blind coach.”

“I see,” Margaret replied. “You can refer to your counselor in any way you want, but everybody here has one. We refer to counselors fairly often, so blind coach may be a little confusing.” Her voice continued to remind Mike of a 1950s’ grammar teacher. It was friendly and firm. After hearing it a while, he felt like sitting up straighter in his chair.

“Yeah, all right, maybe I’ll change,” Norman said.

“It’s up to you, but in any case, please continue your introduction.”

“My wife and I have lived in Duluth for about ten years. We don’t have any kids. I used to think of my players as my kids, but it’s hard to keep in touch with them now.”

Margaret responded, “It is difficult keeping in touch with people from hobbies and jobs we had before losing our sight, but many blind people still enjoy sports. Some of them are bowling, beepball, and downhill skiing.”

“You have blind folks playing ball and skiing?” Norman asked.

“Yes, we do. That’s one of the topics you’ll learn in our recreation class.”

“I enjoy a challenge, but that sounds hazardous.” The last word sounded so gravelly that Mike’s throat felt sore just hearing it.

“You’re right, Norman. It can be hazardous.” Margaret paused briefly and continued. “But I imagine you’ve told your players that sports can be a metaphor for life.”

“I don’t put it exactly that way, but sure, every coach says stuff like that.”

“What do you think of that phrase now, for you and other students?”

Norman thought about the question. When he replied, he flexed some of the muscle in his voice. “Listen, lady, I said that stuff to high school boys, who have more strength and spirit than any group on the planet. I don’t want to make this into a big deal, but things are a little different here and now. It’s one thing to be young and fit. It’s another to be older and blind, especially with fancy ideas like sports being a metaphor for life.”

The tone in Norman’s voice still showed control and some respect, but Mike was glad he was not on the receiving end of the words.

“You’re certain of that?” Margaret asked. “We’re really that different than the young men you coached?”

Mike was impressed with Margaret’s resolve, or outright courage. He probably wouldn’t have questioned Norman’s statement.

“No disrespect, but I’m certain enough.”

“No disrespect taken,” Margaret replied. “You’ll learn more about blind sports next week in the recreation class. For now, I’d like to continue with introductions. Albert, could you go next?”

“Hi, I’m Albert Klausin. I used to sell men’s suits in Rochester. Before that, I sold cars for a few years and drove a bus if you want to go way back. That was ten, maybe fifteen years ago—since I sold suits, I mean.”

Albert’s voice was gentle and content, very different from Norman’s.

Albert continued. “I don’t have a traditional family, but I have a few friends who feel like family. We like to say we’ve adopted each other. My counselor’s been suggesting I come here for a few years. There always seemed to be a reason why I’d put it off. My sight took a turn for the worse a few months ago, so I decided it was time to show up. I’ve figured out a lot of things about living without sight, but I’m looking forward to learning from the experts here.”

“We’re glad to have you, Albert. And thanks for your comment about the expertise of our staff, but I like to think that anyone who’s earned the title of expert is smart enough to keep learning, especially from experienced students like yourself. Mary, could you go next?”

“Sure, I’m Mary Stenson. I’m from Pipestone. My husband and I have lived there all of our lives.”

Margaret interrupted Mary. “I’m sorry, I can barely hear you. Could you speak a little louder?”

Mary cleared her voice and tried speaking up. “Sorry, my husband and I have lived in Pipestone all of our lives. We have two daughters. One is just finishing college and the other is just starting. For the last ten years, I’ve worked as a checkout clerk at the Red Owl grocery store.” Mary’s voice was even softer than Albert’s.

“Thanks, Mary,” Margaret said. “What do you hope to get out of your classes here?”

Mary’s voice became quieter and more hesitant. “I’m different from Albert. I never expected to be here. I’m just …” Her words trailed off. “I’m not really sure. I’m just looking forward to working with all of you.”

“Thanks, Mary. We hear that a lot, about people not expecting to be here. Schools like ours are different from a college or university. At those places, students spend months or years looking at schools. Then, they apply to a few and attend one. Our students don’t do that, but the learning that occurs here is as important as any learning at a university.”

Mike expected he would introduce himself next. He was figuring out what to say when a sound came from the door behind him.

“Hey! Good morning, everybody!” a cheerful voice called out. “I know I’m just a little late, but the people in the kitchen wanted me to bring this tray in.”

Margaret’s voice sounded impatient when she said, “Good morning, George. We were just introducing ourselves. Why don’t you go next?”

“I’d be happy to,” the man called back. The short phrase sounded cheerful, and based on what Mike could see, the man’s movement and chubby shape gave a similar, jolly impression. The man continued speaking. “I’m George Ferguson. I grew up here in Portage Bay, down by the lake. I enjoyed this independent livin’ class so much that I decided to take it again. I may even take it a third time.”

“It’s interesting that you mention decisions,” Margaret said. “We were just talking about that. It’s very generous that you brought in the tray, but it is a decision with implications. I think we can postpone our introductions while you explain the policy about being on time and the decisions students make about time.”

“I’d be happy to. I know a lot about that one. You see, when you can’t see so well, time becomes a lot more important. My favorite example comes from riding the bus. If you’re not on time to the bus stop, you have to wait, sometimes an entire hour. And, I’ll tell ya, that can be a mighty long hour when it’s cold out. Even worse, you’re out there shivering when you could be in a warm bar enjoying a cold beer. My favorite is The Tacklebox, but I’m happy to say that Portage Bay has a respectable variety of drinking establishments. So, the moral of the story is that you need to always be on time. Here, have some treats.”

“George, that was a good answer. Unfortunately, it answered a question I didn’t ask. I asked about the school policy regarding timeliness. Mind trying again?”

“I’d be happy to. Timeliness is truly next to godliness. Hang on, let me put it another way. If you don’t manage your time well, you start doing things like studying at the last minute, or studying so hard at the last minute that you show up a little late for class. At least, that’s what I’ve heard. You shouldn’t really show up late for class because you end up distracting everybody, and the teacher has to repeat stuff. It’s just not a good idea. In some cases, students have gone so far as to skip a class entirely to avoid disrupting the entire class. At least, that’s what I’ve heard. There, did I answer the question this time?”

“Not really. I wasn’t aware that our school policy showed such respect for people who skipped a class, but I’m glad you enlightened us.”

“Happy to.”

“I have the more formal and less creative version of this policy. I’m supposed to read some policies, so I’ll start with this one. But first, please give me the tray and sit down. There’s an open chair next to me.” Margaret took the tray, set it on the table, and pulled out the chair. While George sat down, She took out a paper, put her hands on it, and spoke. “Bridgman School for the Blind encourages you to attend all class sessions for a few reasons. First, this is only a three-month program, so each class session is important.”

Margaret read more policies, but Mike listened less after noticing her hands. Although individual fingers weren’t clear, he could tell her hands were moving over the piece of paper. She was reading aloud from Braille, which he hadn’t seen before. He watched for a while, but a moment later, her dress caught his attention. At first, it looked black, but now, he realized it could be blue, maybe dark blue.

Something else caught his attention. She was looking at the students while her hands were moving. Her eyes appeared as dark dots on a fuzzy face, but he could still tell she was looking around while reading with her fingers. That impressed Mike. He could barely find the bumps in Braille text, much less read them while looking around. He started wondering how much Margaret could see. She clearly noticed him when he walked in. Maybe reading Braille was less disruptive than putting a paper close to her face, or maybe she wanted to show students what they would be doing in a few weeks. He shifted his attention back to what she was saying.

“These policies exist because attending class is a simple yet effective way to succeed. Staff at Bridgman School care about your current and future life. We want to spend time with you and help in any way we can. Therefore, if you have more than two unexcused absences, we will ask to meet with you to discuss this issue. The next rule only applies if you are trying to get our Work Skills Certificate. In that case, you will have to repeat a class after four unexcused absences. This consequence illustrates the importance of attending classes. Our staff sincerely hopes not to ask anyone to repeat a class.”

“But they will,” George said without thinking.

“When we must,” Margaret added.

Mike heard Norman quietly comment, “Sounds like hardball.”

“I’m afraid this session is starting out with more rules and regulations than on the services we want to provide, even the fun we often have. Let’s try returning to the original lesson plan, which means we should finish the introductions. Mike, I think you’re next, and last.”

“Hi, everybody, I’m Mike. I live in the country outside of St. Cloud. Before I came here, I made tractor parts in a factory. I also went to a technical school for a while. I agree with a lot of the things that other people have said. I didn’t expect to be at a school like this, but I’m looking forward to learning as much as I can. I’m not married, but I see my family a lot. I don’t know what else I should say.”

George commented to Mike, “I’ve enjoyed a beer or two with guys who’ve probably used those tractor parts. A couple probably held the same parts you did, since they fix their own machines.”

“George, please, we should return to the lesson plan.”

“All right, sorry.”

Margaret continued. “Next, I’ll give a brief overview of the classes you’ll be taking. It usually takes three months to finish all the classes. Most new students expect to take classes in Braille, mobility, and independent living, which is the one I teach. There are also some classes you may not expect, about financial management, typing, leisure, and counseling to help you adjust to vision loss. You’ll be together for many of your classes, but some classes are individual, such as mobility.”

Margaret explained more about each class, but Mike’s mind wandered, since the descriptions reminded him of similar first day of school presentations he’d heard in high school and technical college. The class in counseling came to mind. He’d spoken with counselors about his vision loss, regarding personal and work issues, but something felt strange about focusing a class on the subject. Then he remembered the crying he’d heard earlier; maybe the counseling class wasn’t so unusual after all. The tone of Margaret’s voice changed, in a way that caught Mike’s attention.

“Time for the little speech I mentioned. I’m not as good at this as other instructors, but please bear with me. Bridgman School for the Blind is named after Laura Bridgman, who was the inspiration for Helen Keller’s education. I’ll describe more about Laura in a couple of weeks. We’ve been helping people like you for over fifty years. In the early days, all we could do was give a few workshops in some borrowed space. These days, we have our own building with more workshops and classes. It still seems like we’re always running low on money and can’t provide as many services as we’d like. We just try to do a little better every year, whether the State gives us more money or not. Lately, we’ve been pretty lucky with grants, so that helps.”

Margaret sipped her coffee, and Mike thought about her voice. It still had a firmness that showed she was in charge but also a sincerity that showed she wanted to help. She put down her cup and slowly moved her gaze to each person at the table, while speaking again. “We’re proud of the students we’ve helped in the last five decades. They’ve also taught us a lot. For example, most students come here ready to learn about getting on with their lives, or at least ready enough. That’s great, but you can still expect some challenges. People react differently to challenges. Some react with humor. There have been moments here where I laughed so hard that breathing became a problem. Other people react to challenges by becoming quiet. Some people talk.” Margaret stood up and started walking around the table.

“Those are pretty easy reactions for us to work with. A few are more dramatic. For good reasons, some students need to cry once in a while. That’s not surprising. This may sound odd, but I have a little advice about crying. If you feel the urge, don’t make much of an effort to hold it in. Usually, that just makes it burst out later. I recommend you excuse yourself if you can, find a comfortable place, and let it out. We’ll talk more about this in the counseling class.” She stopped walking around the table, right behind Norman.

“There’s one more dramatic response I need to talk about. Some students respond to challenges with anger. Responding with anger makes at least as much sense as other responses. And in many ways, we encourage students to let out their anger just like we encourage students to let out their sadness. But we are more careful with anger. If any student lets out anger in ways that threatens anybody or anything, we will calm the situation. This place must feel safe. Having said all this, another pattern we’ve noticed is that angry outbreaks are rare. Crying is more common. With all these reactions, students usually work through them and carry on very well with their classes. Any questions?”

For a few seconds, nobody responded.

“I’m feeling kind of weepy,” George joked. “Can we take a break?”

Everyone laughed, including Margaret, who replied, “We’ve been going for about an hour, so yes, everyone can have a short break, except for George.” Her tone became more serious when she added. “I would like to talk to you for a moment.”

Mike stood up and walked out of the classroom. He also thought about the lecture George was going to get and similar lectures he’d personally received years ago.

Mike arrived in the dayroom and looked around. There was a big easy chair next to him, couches along the walls, and a few people sitting. He noticed the television and wondered if it was one of those new color ones. A deep voice interrupted his thoughts. “Hey, Mike, that you?”

“Yeah, it’s me, Norman,” Mike answered and then asked, “What do you think of this place so far?”

“Not bad. It’s a little different being a student again, since being in school has usually meant being a coach. I can’t complain, though. Seems like a good school.”

Mike agreed and Norman asked, “So what do you do for fun in Central Minnesota? Ever play football?”

“Tried it, but it wasn’t a good fit.”

“Wrestling?”

“Not really.”

“Basketball, track, cheerleading?”

Mike smiled and answered, “Didn’t have the legs.”

Norman grunted a laugh.

“So, is there any sport you enjoy?”

“Well, there is one winter sport my friends and I try once in a while. It’s a form of tag.”

“Winter tag?” Norman slowly spoke each word.

“Yeah, with snowmobiles.”

“Winter tag with snowmobiles. I don’t imagine you had much of a crowd watching the game, or cheerleaders.”

“Never did, never figured out why, either,” Mike replied, trying to hold back a laugh. “It’s a great sport.”

Norman sighed and shook his head. “Tag with snowmobiles? Sounds hazardous.”

“It wasn’t that bad. The snowmobiles didn’t actually touch, usually. We used snowballs to tag each other. After all, we didn’t want to be reckless.”

“Right,” Norman said. “It still sounds hazardous.”

“We like to think of it as more of an adventure sport than a hazard,” Mike said. “It’s not too different from football that way.”

“Well, maybe,” Norman replied, sounding unconvinced.

“I guess I like a little adventure. Haven’t you ever thought of sports as a metaphor for life?” Mike asked. The words left his mouth before he realized their risk.

“Don’t start with me,” Norman grumbled.

Mike thought about apologizing for the joke and how replying too fast with jokes was an old risky habit. Then again, Norman might not even think of his comment as a joke. Mike chose a safe response.

“Fair enough. Truth is, I played some football in high school and an occasional softball game. It’s just that, usually, I end up in games like snowmobile tag.”

Another voice joined the conversation. “I heard about another creative sport from around St. Cloud, goes back a few years.” The voice came from George. Mike was surprised and relieved that his lecture had been short.

George continued. “It’s quite an action-packed game, really. You got the big and clean team, the small and scrappy team, and you definitely got crowds cheering. No cheerleaders, though.”

Norman sighed. “I’m not sure I want to know what this sport is.”

“Aw, c’mon, Coach, give it a guess,” George replied.

“Don’t call me Coach. That’s only for my boys,” grumbled Norman.

“How about you, Mikey? Any ideas?”

Mike was intrigued. It was rare that someone described a creative sport from his hometown that he hadn’t heard of. “I’m not sure. A lot of sports have different teams and crowds. Could be a demolition derby or dog show. Could you describe some more?”

“I’d be happy to. One thing’s for sure, this ain’t no dog show. Cars are sometimes demolished in the process, and come to think of it, dogs are involved once in a while. There, that’s your hint.”

Mike felt an answer coming. “One small question. What makes the crowds cheer?”

“Sorry, you’ve already had your hint. Give it a guess.”

“Just for the fun of it, could I make a partial guess?”

“Not sure. Make your guess and we’ll see,” George replied, enjoying the game.

“My grandpa had a small farm, and once in a while, he’d head into the woods, trying not to be noticed. If someone asked where he went, he’d smile a little and say he had to ‘go cook.’ That have something to do with it?”

George laughed a knowing laugh. “Yeah, that has something to do with it.”

“What is it?” Norman asked, with surprising interest.

George’s laugh faded as he answered, “It’s mostly water, some corn, bit of yeast, and some very careful cooking. The sporty part involved guys in the country, most of the time.”

“Well, I’m not from the country. Are you going to tell me what this is about?”

A loud voice broke into the conversation. “Anyone here for the orientation class, our break is almost over. Please start returning to Room 5.” All three knew it was Margaret.

“It’s about cooking,” Mike replied to Norman, heading back to the room as the other two men followed.

“Cooking? You guys are not talking about cooking.”

“Sure we are,” George added.

“Cooking in the woods?”

“Creative cooking in the woods,” George clarified.

“Creative cooking in the woods with demolished cars and cheering crowds?” Norman asked, sounding impatient.

“And no cheerleaders,” Mike added and entered Room 5.

George laughed loud enough that he received a stern comment from Margaret. “George, please.”

“Little humor, not too much,” Mike said and smiled.

George grunted another laugh.

“You guys are going to drive me nuts,” Norman muttered while finding his chair.

The break had been more refreshing than Mike had expected, but he still felt strange sitting in a classroom where he would relearn the basics. The rest of the day reminded him of other first days in other classrooms. A lot of important information was presented about classes, teachers, and the school. But just like other first days at school, Mike retained little of it.

Several hours later, as he walked out of Bridgman’s, Mike thought about his first day at school and the people he’d met. The people seemed all right, but he was still looking forward to finishing school and going home to the country. These thoughts continued until he saw the two neon signs and focused on returning safely to Mariner’s Motel.