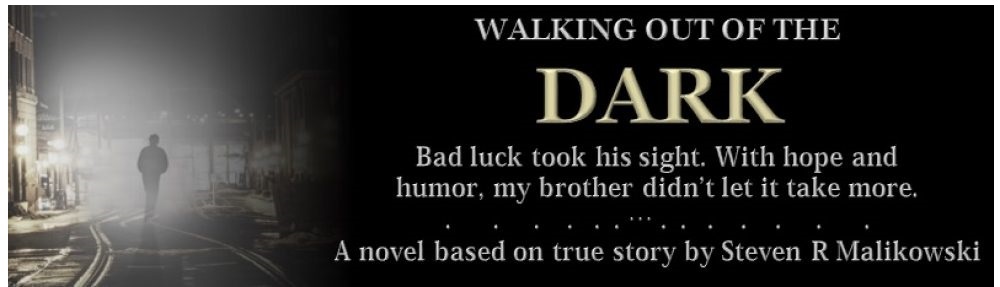

This page shows the first draft of the first chapter of my next book. It’ll be similar to the book described on this site, but instead of describing how my brother dealt with blindness, my next book will describe with how I’m dealing with cancer and how I eventually cycled across the US with a wonderful group from Adventure Cycling. The next book also starts a lot faster, at least I hope it does.

Chapter 1: Three Years

September, 2017

I was 51 years old, ran a few marathons, and loved cycling for 100s of miles. At the moment, I wanted to ask Dr. Carrington if I’d live 15 more years, 10, or less. Unfortunately, I couldn’t ask that direct question because I knew how she’d answer. Like most oncologists, she’s very bright and compassionate. That comes from working with many newly diagnosed cancer patients, like me. They answer direct questions about life expectancy with elusive answers.

Sometimes, it’s the over-used phrase, “Every case is different.” Other times, it’s more clever, like “Before I answer, I want to know why you’re asking. There are different answers if you want to have children, buy a house, or travel the world.”

I’d become clever too, so I asked, “On average, how long do men with my type of prostate cancer live?”

She paused at that question. It didn’t give her room for a vague and compassionate reply, although her reply was still gentle.

“You have every reason to think that you’ll live longer than average.”

“How long?” I asked with gentle firmness.

“Three years.”

My thoughts stopped. I looked away and leaned back in my chair. The idea that I would live for three years wasn’t unexpected. It was unimaginable.

Until a year ago, all I knew about the prostate gland is that only men have it. Since being diagnosed with prostate cancer, I’d learned a lot more. For starters, it’s most active when men are having a really good time, during sex. Now, it felt like that stupid little sex gland was going to kill me in three years.

She brought me back by firmly repeating, “But you have every reason to think that you’ll live longer.”

I barely heard the words. Mary’s hand gently held mine. We’d been dating for about a year. I’d been diagnosed with cancer soon before we met, and it kept getting worse. I was impressed that she stayed with me. She was a successful technical writer, in downtown Minneapolis. I’d often meet her downtown, and we’d enjoy the city together.

My face tightened up, and tears fell down. Emotions were harder to control because of the cancer treatment I was already on. Prostate cells must have testosterone, whether they’re healthy or cancerous. So like most guys in my situation, my testosterone was shut off soon after I was diagnosed.

There are a few symptoms of having no testosterone. You might guess the first one. My sex drive fell to nearly nothing. I’d sometimes joke that if a dozen supermodels were wearing bikinis in front of a new bike, I’d ask them to get out of the way, so I could see the bike.

Other symptoms of having no testosterone are similar to what women go through during menopause, like hot flashes. I have three sisters, and they’re all older than me. After my testosterone was shut off, I texted them with a question, “Could you give your little brother tips for dealing with menopause, especially hot flashes?”

I learned how to manage those symptoms well enough, but the symptom that stayed out of control was more emotions, mostly sad ones. I’ve always been one of those sensitive types, enjoying theatre and literature and being bored by trucks and football. But without testosterone, I’d become a guy who cried too quickly. Some people can let tears roll down and barely change the look on their face. Sometimes, they even show more compassion or sincerity with those tears. I don’t know how they do it, but I envy them.

Maybe they’re just stronger or calmer than me and feel no shame or indignity in tears. Maybe they’ve finished the hard work of resolving unsettled emotions and accept that tears are part of being a decent, vulnerable human. The people I’m thinking of have all seen hard times, but maybe they haven’t had to accept that their flawed yet wonderful life could end in a few short years.

I still hoped to cycle across more countries, write more stories, and help more people. I still hoped to feel deep love again, since I’d only known it once, in London. I still had family who called me Little Brother. I was the youngest, and it felt like I would go first. I was nowhere near accepting that. It was too sad, and the process of my strong body fading was too scary. Each tear told me I must accept all that, so I fought each one with everything I had. I usually lost the fight, and when I did, the indignity made me cry more.

These thoughts are part of my emotions getting out of control. Fears and frustrations spin around in my head. I wanted them to stop, to focus, and ask Dr. Carrington some questions. But when I tried, my voice wavered, choked up, and the words stopped. I’d been a professor at the University of London who gave lectures to hundreds of medical students in an auditorium, but now in this small office, I couldn’t even talk.

More tears came down, and the amplified emotions convinced me there was no hope. Mary held my hand tighter, and Dr. Carrington handed me a box of tissues. I tried talking again and failed again, a few times. Finally, I found a short question that mattered and forced it out.

“What can I do?”

After asking, I realized the question had a few meanings. It could ask what I’d be capable of as a man with advanced cancer. It could ask what life would be like during my few remaining years, or it could ask how I could fight. I didn’t know which meaning mattered. Maybe I was also asking Dr. Carrington to decide, which she did.

“I can give you clear clinical data that people who embrace life live longer. You need to get on your bike.”

Her answer impressed me. She knew I value clear and careful research, came from having been a Lecturer and running a research group. And like anyone who knew me, she knew I loved to cycle. Mary gripped my hand harder for a moment.

The tears slowed and more words came out. “I’d do that anyway. What else can I do?”

“Give yourself some time to take this in. We’re going to review your test results with the Mayo Clinic and find the best treatment.”

I felt certain that the best treatment would be chemo. I’d never had it, but I knew enough that I’d be sleeping and puking instead of cycling and laughing. I’ve never been good at sitting still, so lying around and throwing up a lot worried me. It was even worse since laughing and cycling are two parts of life that I enjoy most. Overall, chemo felt like it would be months of what I was worst at without the joy of what I was good at. And during those months, my emotions would continue to flare up as they already had. I suddenly wanted to leave, so I thanked Dr. Carrington for her answers, stood up, put on my coat, and collected my pen and notepad.

“Stephen,” said Dr. Carrington.

I faced her. She stood up and gave me a hug. The damn tears kept coming.

I appreciated that she didn’t repeat the part that I should expect to live longer. She already said that. I understood, but right now, I couldn’t fight the tears and had to let them out. Dr. Carrington knew that.

I still had to get out of there, so I walked to the door, and Mary followed. Before walking out, I paused, turned, and thanked Dr. Carrington again. That was purely instinct, maybe manners or dignity.

After the tears slowed, she asked a simple question. “What do you want to do now? We could go to my place, yours, or anything else.”

Without thinking, I answered, “I want to go to Sue’s resort.” My sister Sue owned a small resort with her husband. It was closed for the season, but after hearing my news, I was certain she’d give us a cabin for the weekend. I sent Sue a text:

I just learned that my cancer is worse, might only have a few years. I’d like to get away for the weekend. Could Mary & I stay in one of your cabins?

About a minute later, she replied.

Of course.

We drove to each of our apartments and quickly packed. While tossing clothes into a suitcase, I felt relieved that we were getting away for the weekend, which felt like I was getting away from cancer. Even if it was a false or temporary hope, I needed the respite.

The sun was setting as we drove north, which helped me relax. Sometimes, I talked more calmly about this new lifestyle. Sometimes, I cried, and other times, we just watched the countryside change from the city, to farmland, to the forests of northern Minnesota. During one of my calm moments, I sent a similar text to my other two sisters and to my brother.

I just learned that my cancer is worse, might only have a few years. Mary & I are driving to Sue’s resort for the weekend. Could you stop by? Hope so.

Within minutes, they all said they’d be there. After reaching Brainerd, we stopped at a red light and saw a grocery store. Mary asked, “How about stopping at that store? We’ll need some things for the weekend.” She smiled a little and added, “like coffee and maybe even bran muffins.”

She knew I loved both. I smiled back and replied, “Now, you’re just trying to turn me on.”

“Good,” she said. The light turned green, and she drove toward the store. I normally go to large grocery stores because I live in a large city. Brainerd is a small city, so the grocery store was smaller than what I’m used to, which felt much more personal. Even the signs showing what was on sale felt more personal. Instead of large signs with elaborate pictures of the apples that were on sale, there was a handwritten sign saying, “Tasty apples, 5 for a buck.”

“I need to buy some of those apples,” I said to Mary.

“But you don’t really like apples,” she replied.

“With a cute sign like that, I’m going to like apples,” I said, and we picked out five apples, with little jokes about how the other kept picking out a much better apple. We chose other groceries in a similar style, until we turned a corner, and I heard her say, “The next choice is entirely up to you.”

The coffee section was in front of us. She knew that I loved looking at all the different beans, blends, and flavors. I smiled, quickly stepped closer to the shelves of coffee, and looked for the best options. “Folgers, yum,” I said touching the label. “But we also have Maxwell House, and look, a generic brand.”

“Well, we are in a small store,” said Mary.

“Yes, we are, and I’m thoroughly enjoying it.” I grabbed the generic brand and dropped it into the cart.

“All we have left to get is muffins,” Mary said, “and just in case they don’t have your bran muffins, we might want to think about a backup plan. What else might work?”

“Any muffin where the dough resembled cement mix. I like hearty muffins.”

I pushed the cart toward the bakery section, and the first muffins we saw were bran muffins. “I’ve always liked these small-town grocery stores,” I said while putting a box of muffins into our cart.

After driving away from the grocery store, we talked about the beauty of the lakes at sunset, and laughed at the important little things in our lives—like her cat, my bikes, and our family and friends. A short while later, we were at Sue’s resort. Mary parked by the resort office, and we walked inside.

I’ve walked into that office many times, and each time, my sister Sue walks toward me with a smile and gives me a hug. She wasn’t smiling this time. Her face looked somber. She walked toward me, and we hugged. My tears and tight throat soon followed. I forced out some words, “I need time in a cabin to think.”

“That’s fine,” replied Sue. She held the hug for a moment more, let go, and gave me a cabin key. “You’re in number 5. I’ll stop by later.”

Mary and I drove to the cabin, brought our bags inside, and put away the groceries. Once again, my emotions quickly switched. The tears faded, and I showed her around the cabin. It had a cozy kitchen, two bedrooms, and walls of knotty pine.

All that felt good, but my favorite part was the fireplace, even though it burned gas instead of wood. I started the fake fire, and Mary sat next to me, on the floor. I leaned against her, watched the fire, and let my thoughts wander. They kept returning to cancer. After a while, I had to think of something else, so I asked “Could I show you some stars?”

“Yes please,” she said with a slight English accent. That little phrase said a lot. She picked it up from me, and I’d picked it up from living in London for seven years, returned about two years prior. I always liked good manners, so saying “please” more often was a bit of Britain that I brought back with me. Hearing it from Mary brought me back even more. She’d never been overseas, so I hoped to show her London someday.

We stepped outside on the concrete patio in front of the cabin. Since we were far from the lights of a city, more stars appeared, and they were brighter. With so many stars, it took me a while to recognize some constellations. Eventually, I found the common constellations like the Big Dipper, Little Dipper, and Draco, which is the dragon that winds between the dippers. I wanted to show her more, but first, I asked Mary, “Would you mind joining me in a better way to see the stars?”

She said yes, and I laid down on the concrete patio, looking up. She laughed a little and laid next to me. I forgot about cancer and showed Mary Cassiopeia the queen, Cepheus the king, and Lyra the harp. “Those are fun, but my favorite star is Arcturus. I like how the name tells you how to find it. You just follow the arc in the handle of the Big Dipper, look for some dark space, and you’ll see a bright light. That’s Arcturus, a red supergiant. It’s in the constellation Bootes, the shepherd. I’ve always liked having a shepherd in the sky, and if you look closely at Arcturus, you’ll see reds and blues flicker from her, beautiful.”

“Cool,” which is another small phrase that described Mary. She said less than other women I’d dated. I was looking for more constellations when we heard Sue walking toward us.

“Hi there,” I called out.

“Where are you?” she asked while walking closer.

“Down here. Care to join us?”

Sue laughed, said “sure,” and laid down on the concrete next to me. We talked about how we could see the Milky Way out here, which wasn’t visible in the city. But after a while, I told Sue what Dr. Carrington had said earlier that day, crying less than expected. Looking at the stars, instead of into Sue’s eyes, made it easier to talk.

After I finished, Sue asked, “So before you saw Dr. Carrington, you thought the cancer could be cured with radiation, but now it can’t.”

“Yes,” I answered.

“Why can’t they radiate it now?” Sue asked.

“We didn’t talk about that a lot, but I think it’s because radiation only works with a small target. Now, my cancer is too spread out.”

Mary added, “When it’s outside of his pelvis, radiation would also hurt other organs.”

“Where exactly is it?” Sue asked.

“It’s near my kidneys, in my lymphatic system. That’s a secondary drainage system.” I answered. My voice wavered again when I added, “It’s also a place where cancer can move fast.”

“What’s next?” asked Sue.

The question scared me, since I felt certain chemo was next. My throat tightened, and I didn’t want to fight it by trying to answer. I rolled my head toward Mary and glanced toward Sue, hoping Mary would know that I wanted her to answer the question.

She did understand and said, “Dr. Carrington is going to check with the Mayo Clinic to see which treatment is best.”

“Probably chemo.” The words came out of me slowly and calmly, which was surprising. I sighed and added, “I’ll do whatever they say, but I don’t like chemo. It’ll make me lay around a lot, which I’m not good at. I also don’t like puking, and I kinda like my hair.”

We returned to silently enjoying the stars for a while. My phone rang. I answered it and heard, “Hi Stephen, this is Dr. Carrington. I just wanted to check on you. How’re you doing?”

I told her about being at the resort. She said that was a great idea, and the conversation ended a moment later. After hanging up, I looked at the time on my phone. It was 9:00 PM. “That was Dr. Carrington. I’m amazed she called at 9:00 at night.”

They commented how impressive Dr. Carrington was, but my emotions got out of control again, with anxiety. My voice waivered when I said, “I’m not sure if I should feel impressed or worried. I mean, would she call if my outlook was good?”

“Yes, she might,” Mary replied.

“She’s right, Steve,” said Sue. My family called me Steve because I didn’t go by Stephen until living in London. Sue continued, “I understand why you’re scared. You should be. This is cancer, but when you met with Dr. Carrington this morning, she did say that you have every reason to live longer.”

“Twice,” Mary gently added.

“You’re right, but my cancer keeps on going further than they say it will.”

“That is scary,” Sue replied, “but that doesn’t mean they can’t stop it.” She paused and rolled her head toward me. “I’m sorry. Maybe it’s best for you to feel scared for a little while.”

“I don’t know what’s best, Sue.” I replied. “Enjoying life is still important, more important than ever. Maybe you’re right. Maybe I need to be scared for a while.” I wiped away some tears.

Sue put her hand on my arm and replied, “Sounds good, Steve.” A moment later, she added, “How’re you doing, Mary? This is gotta be hard on you too.”

“I’m okay,” Mary said quietly. She sighed and continued, “I know it can happen to anybody, but it still doesn’t feel right it’s happened to Stephen. I mean, he does everything a guy should. He loves veggies, laughs a lot, and even though his cycling is just a little excessive, it’s still good exercise.”

I smiled at the remark but felt sad when I heard Mary’s voice break up, from tears.

“But this still happens to him. It just sucks.”

Sue agreed. I held Mary’s hand for a moment and said, “Maybe we should call it a night, been a tough day.”

We all stood up. Sue hugged me and walked back to her house, which was part of the office we stopped by earlier. Mary and I walked inside the cabin and got ready for bed. For me, that used to involve flossing and brushing. Now, it included pills to keep my testosterone off and pills to help me sleep, over-the-counter sleep aids.

Without those sleeping pills, it would take me hours to fall asleep, and after I did, I would wake up a few times worrying. Without eight or nine hours of sleep, my emotions were even harder to control. It felt reasonable to take sleeping pills every night, but it still felt strange to take so many pills. A year before, I rarely took any. I tried dismissing these thoughts, brushed my teeth, took the pills, and got in bed with Mary.

Without thinking, I laid on my side next to her and rested my head on her chest, saying nothing. She put an arm over me and leaned close. I never felt such a strong need to be held.

“I’m not reckless or fearless, but I’ve never gotten scared easily, not of the dark when I was a kid, not of cycling in London, or cycling alone for 1,000 miles.”

I stopped talking when the tears started. They rolled down my face, and after reaching her skin, she leaned toward me more. My throat tightened up, but I’d learned how to force out some words.

“I’m scared now. This isn’t like losing money or like when my brother lost his sight.” I shook and cried harder. “This is everything.”

Mary held me harder and softly said, “I know what it’s like to be scared. Cycling in traffic scares the shit out of me.”

Her embrace and words made me feel better, although I instinctively cringed at the reference to shit. She continued. “I know you’re scared but nobody has said you’re going to lose everything anytime soon. Dr. Carrington is a bright woman, and she said you have every reason to think you’ll live for many years. And by then, there will be new treatments.”

I took a deep breath and let out a long sigh.

“Just try not to be too scared right now. You’ve always been good at trying.”

“You’re a pretty smart girlfriend.” I meant that. Even though some of her words weren’t the ones I’d use. She was a good woman and girlfriend.

“Thank you,” she replied, leaned toward her nightstand, and turned out the light. “Now, let’s go to sleep.”

Even after taking sleeping pills, I still woke up a few times. Mary had become used to that, so she didn’t notice when I woke up around 7:00, got out of bed, and walked out of the bedroom—softly closing the bedroom door behind me. I walked into the kitchen, ran my hand over my head, and noticed that my erratic emotions had calmed down, which usually happened after a good night’s sleep. I felt like making Mary a treat, but coffee always came first. I added grounds and water to the machine, pressed the start button, and felt a bit more awake from just knowing coffee was coming soon.

Feeling more awake also made me feel happier about making a treat for Mary, as I imagined the smile on her face when she woke up and saw its colors. The treat started with apples. I took a couple out of the fridge, gave them a quick wash, and cut them into bite-sized pieces. Next, I took a large plate out of the cupboard and placed the cut apples on the outer ring of the plate, in a circle. Oranges were next. I took a couple out of the fridge, peeled them, pulled apart the pieces, and placed some on the plate, in a ring just inside the apples.

The oranges were almost all in place when I suddenly stopped, due to a feint but important sound. The coffee machine had made it’s very first gurgle, meaning the first cup could be poured. I dropped the remaining orange pieces on the countertop, pulled a coffee cup from the cupboard, and walked to the coffee pot.

While pouring coffee into the cup, I said to myself, “Cancer is a bummer.” I lifted the cup up to my chin, paused, and added, “but it does make you appreciate life’s amazing little wonders, even this generic stuff.” I breathed in deep through my nose and enjoyed the aroma. Finally, I sipped it, and a small smile followed. With that critical part of the morning over, it was time to get back to the oranges.

I picked the pieces I dropped a moment ago and placed them next to the others on the plate, completing a circle of oranges inside the apples. Grapes were the last step. I took a bunch from the fridge, rinsed them off, and placed them in the middle of the plate. It was now complete, a ring of sliced apples on the outer ring of the plate, oranges inside that, and grapes in the middle. It would have been nice to have some blackberries and strawberries, but this was ok.

I’m actually a lousy cook. Over many years, I’d bought Cooking for Dummies a few times, became overwhelmed at the complex recipes, and donated each copy to a local library. But I can make a nice fruit plate. I sipped my coffee and took a moment to enjoy the sight of the fruit plate, another one of life’s little wonders.

I poured a cup of coffee for Mary, finished mine, and filled it up. Everything for my morning surprise was ready, but there was no tray to carry it all. I had to settle for a large cutting board. It was made of wood, so it looked nice with the coffee cups and fruit on top. But now, the challenge was getting it to the bedroom without anything sliding off the board. I lifted the loaded cutting board off the kitchen counter, walked slowly to the bedroom, and imagined hot coffee landing on my bare feet. “Stephen,” I said to myself, “don’t focus on what can go wrong, another lesson from your little health problem.”

Considering the emotions I’d been struggling with, it felt strange hearing that wise comment from my own voice, but I still followed the advice. Holding the tray with one hand, I opened the bedroom door with the other. The tray stayed stable, and I looked at Mary. She was still asleep, as I hoped. I set the coffee and fruit plate on her nightstand, bent over, and kissed her on the cheek. She smiled, opened her eyes, and reached out for a hug. I lay down, gave her a hug, and we held each other for a while.

As we quietly lay there, I thought about what usually happened next. For the last few decades of my life, sex was next, especially in a cabin, but that was another part of life that changed with advanced cancer. For the last year, my sex drive dropped almost as low as my testosterone. It still happened, but just a day ago, I’d learned that my cancer had spread to stage 4. Even with that, you can’t help but ignore decades of experience, which was another case of complicated or contradictory emotions. I suspected Mary had similar thoughts.

I wanted to say something like, “We both know what usually happens next.” But I couldn’t, just the thought made my throat tighten up. That little phrase felt like describing a new weakness, which I couldn’t handle right now. Saying it would lead to tears, and that would spoil this nice morning.

I quietly sighed and said, “I have a treat for you.”

“I smelled the coffee, thank you.” That made me think that she hadn’t seen the fruit plate yet, so I asked, “Would you mind if I gave you a little gift?”

“Yes please.”

I sat up, reached for the fruit plate, and set it on my lap. Her smile was just what I hoped for.

“Thank you,” she said. “I love the colors.”

I reached up and pulled the curtain open, to let in some sunlight. Nobody else was at the resort, so there was no risk of someone looking inside. The light bounced off the knotty pine walls, gave the room a wonderful glow, and we enjoyed the fruit plate without saying much. During one of the silent moments, I realized that this could be one way to beat cancer. Even if it took more of my body, I’d try to hang on to my spirit, with wonderful moments like this.

“What time do you think your family will be here?” asked Mary.

“Good question, I love them tremendously, but they can be a painfully early bunch.” I looked at a clock on my nightstand. “Wow, it’s already 8:00.”

“Did you ask what time they’d be here?”

“No, I forgot.”

“Anything on your phone?” she asked.

I picked up my phone and answered, “Yeah, I have a text from Nancy. ‘Good morning little brother. We’re thinking about being there around 9:30, hope that’s ok.’”

“Do you think it would be rude if I called her back, said it’s not ok, and that we’d rather lay in bed until noon?”

“Probably not,” Mary answered.

“But what if I really don’t want to get out of bed?” I asked playfully.

“It might be a little strange if everybody shows up and has to come in here,” she replied in a similar tone.

“Maybe, maybe not.” I said, keeping the little battle of wits going.

“How about if I tempt you out of bed by mentioning the bran muffins?” she asked.

“Oh yeah!” I said, jumping out of bed. I smiled, looked at her, said “I forgot about that,” and dashed into the kitchen. Mary laughed, and when I was opening the fridge, she called out, “Be sure to save me one.”

“You better come quick,” I replied, while putting a couple of muffins into the microwave to warm them up. I also opened the curtains, so we could see the lake.

We enjoyed a muffin, more coffee, and the view of the lake. After taking the last bight from my muffin, I asked, “Would you like to walk to the water?”

“That’d be nice,” she replied. We put on warmer clothes, stepped outside, and walked toward the beach.

For several steps, we quietly enjoyed the sunny morning, until I felt something unusual. “This is weird, but little things are more intense than before, much more. The breeze in the trees, the morning sun, and of course, the birds.”

“You’ve always liked the birds,” she said while reaching for my hand. I took it, and we walked closer to the lake.

“When’s the last time you were on a dock?” I asked, knowing she hadn’t been to cabins much.

“It was probably during the sailing class I took in college. The dock was probably the best part.” She’d told me about the sailing class before, so the last comment was a reference that she wasn’t comfortable sailing.

We stepped on the dock, and after a few steps, I paused. “Do you hear that?” I asked pointing toward a stand of reeds by the dock. “Those are red-winged blackbirds, my favorite.” We listened to the unique tweedle-dee song of the birds for a moment, and I added, “When I lived in London, I missed that sound so much that I set up my phone to play it when I got a text.”

We slowly walked down the dock, still holding hands. “That weird feeling is still with me.” I said slowly, “It’s strange, but in a good way. Those birds sound a lot clearer. The fear of cancer must be doing something to me, even though I feel calm.” We took a few more steps, and I gestured toward the water. “The light bouncing off the water seems brighter, and the air seems fresher.”

We stopped at the end of the dock. I slowly looked around and appreciated the sensations that had become more intense. “Wow, I didn’t expect anything like this. It’s not surreal or a hallucination, but it’s different, more intense.”

I sighed, stopped looking around, and gently hugged Mary. “Thanks for being here,” I whispered.

“Of course, she whispered back.”

The sensation of her body next to me was also more intense. I enjoyed it for a long moment, but reality came back to me. “I guess we should get ready for my family to show up.”

We walked back to the cabin, and my family showed up soon after. My family’s always been close, and tough times made us closer. In the 1970s, my brother lost his sight at age 26. In the 1990s, one of my nieces was killed by a reckless driver. And after that, we all saw our parents pass away. But we still laughed, hard. One of our favorite family stories was a Thanksgiving dinner when our dad had to leave the table because he was laughing so hard that breathing became a problem, which made us laugh more. Of course, we argued sometimes, but that seemed long ago. In recent years, we talked, cried, and cared more deeply. All that made me want to see them even more now, but something was different this time.

My family arrived in groups of two or three, at different times, and each time a group arrived, I had to tell the story of my cancer again. They listened to the story with compassion, asked questions, and usually cried. That made me cry when I answered. I appreciated that each one dropped everything and showed up, but talking about cancer so much wore me down. They left around sunset. Mary and I spent another quiet night in the cabin and drove back to St. Paul the next morning.

During the drive, I felt that getting away for the weekend helped, but now, I was going back to the reality of a tough lifestyle. I also felt unsettled because I’d been sitting around too much. I really wanted to get on my bike.